When I first worked managing reader comments at NYTimes.com, the news was the subject and the comments were the reaction. But tools like Epinions and Blogger flipped the world so that the reactions became the substance. This made Mark Zuckerberg a billionaire and also led Time magazine to declare "You" the Person of the Year in 2006.

It also heralded the slow (or maybe not so slow) degradation of the line between fact and feeling in the public square. What started as inclusion—or "presence" as we called it around 1999 when we marveled that you could turn on the houselights and let the audience see each other—became disregulation, entitlement and, worst of all, another vector for the powerful to manipulate the consumers.

If you've ever had to translate policy work into the urgent, human narrative of social change, this roadmap from Sarah Jane Staats and Todd Moss of Energy for Growth Hub can help you. Some of their humble, practical insights that I especially recommend include:

• Policy influence isn’t “direct, straightforward, or predictable." Multiple factors are in play.

• We “influence" and help “instigate” change. We’re not the single cause.

As a result, “attribution is messy.” Policy ideas, even the best most impactful ones, don’t usually have clear KPIs.

• To assess effective policy proposals, we can invest more in “tracking demand from policymakers.”

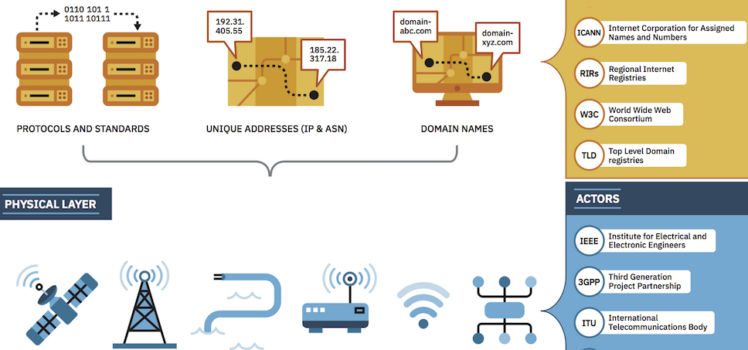

During 2021, I had the privilege of editing this report by Dr. Niels ten Oever, on the odd, risky, and critical links between human rights and the management of the internet's infrastructure—the matrix of services, connections and rules that keep the internet running.

The evolution and unique culture of internet infrastructure is as interesting as it is revealing about the dangerous moment we're in now. As we say in the report, "The commercialization and privatization of the internet that began in the 1990s was expected to bring about innovation and competition. In practice, it has led to the emergence of oligopolies."

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed deep structural problems that go far beyond conventional ideas of public health, not least the impacts of pervasive inequality and racism. Civil society is mobilising to adapt and respond. Our ability to drive change will depend in part on our ability to communicate vital information in effective ways, harnessing the power of data and digital technology. The emergency has shown that the right information delivered in the right way can prompt people to change their individual behaviours and collectively save lives all over the world.

The iconic "Flatten the Curve" graph, which encouraged people everywhere to help contain the spread of COVID-19, is a case in point. It shows how measures such as hand-washing and social distancing can squash the expected peak of the pandemic, and keep infection numbers low enough for healthcare systems to manage. This simple public health chart, which originated in specialist journals and reports, was widely shared by traditional newspapers and magazines, then refined to clarify the message even further, translated into many languages, and creatively reworked into animations, cartoons and even cat videos.

A colleague in the data and human rights world asked friends and followers what international leaders need to hear right now about the state of human rights around the globe.

I told him that if I could draw on my own experience to ask an international body to do one thing, it would be to confront and address the global delinquency in data governance.