Net Neutrality Victory in U.S. Can Help Rewire International Policies

Consumers, campaigners and champions of free speech everywhere won a huge victory last week when United States regulators voted in favor of net neutrality rules, reclassifying broadband internet in the U.S. as a “common carriage” service open to all customers.

Consumers, campaigners and champions of free speech everywhere won a huge victory last week when United States regulators voted in favor of net neutrality rules, reclassifying broadband internet in the U.S. as a “common carriage” service open to all customers.

Practically speaking, that means internet providers cannot impose a “slow lane” or a toll gate on users based on the information or sources they are trying to reach. As law professor Tim Wu, who first coined the term “net neutrality,” put it, the rule:

… makes it very clear to the phone and cable companies: You can’t block anything. You know, you might not like a website that says Verizon’s too expensive; you can’t block that. … you can’t go around and say, ‘Hey, if you don’t want to be slowed down, you need to pay us more money’ … like kind of a protection scheme.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) decision comes 13 months after a legal setback for net neutrality, when an appeals court sided with Verizon in a challenge to existing rules. The new rules, approved in a 3-2 vote by the FCC commissioners, affirm that broadband internet is to be treated as a “telecommunications service,” not as an “information service” such as premium cable or other subscription content.

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler called the decision “an irrefutable reflection of the principle that no one, whether government or corporate, should control free and open access to the Internet.”

The debate between corporations and open internet advocates will continue in the U.S., but in most international telecom markets the net neutrality discussion is less evolved and as or more urgent.

In its Web Index ranking 86 countries, the World Wide Web Foundation found that 74% “lack clear and effective net neutrality rules and/or show evidence of price discrimination.” Foundation director and Web creator Sir Tim Berners-Lee, told European lawmakers last month that, “In 95% of countries surveyed where there are no net neutrality laws, there is emerging evidence of traffic discrimination – meaning the temptation for companies or governments to interfere seems overwhelming.

So, even as internet users living in developing countries or under repressive regimes confront problems with basic access, freedom of speech or freedom from surveillance, the risks of a non-neutral net await them, including policies that enable content blocking and price discrimination, or policy vacuums that cede control of the information pipeline to actors who are biased or worse.

On the night of Thursday’s FCC ruling, I happened to be at a discussion on human rights and video co-hosted by Neon and WITNESS, pioneers in multimedia activism and global campaigners for net neutrality. Panelist Sam Gregory, WITNESS’ program director, told me that putting the FCC announcement into the international context “is just a matter of translation.”

In a country without economic or political stability, Gregory said, “it’s often the people already marginalized in terms of resources, access, money for bandwidth, who we want to have the ability to make their voice heard, and the people whose stories most need to be told are often the ones already in conflict with corporate or government interests.”

Panelist Nicole Wong, former White House tech expert and Google VP, said the new U.S. policy can help push other countries toward greater openness over time. “When you declare that open, equal and broad access is the standard, it sends a message,” she said, even to regimes where freedom of access and expression are “anathema,” like Turkey.

David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, echoed Wong in his public statement on the FCC decision and its power as model for other governments.

Even governments seeking to widen internet access can create unintended obstacles to net neutrality. As Ethan Zuckerman noted in our 2014 blog post, countries that turn to Facebook or Google to help un-wired communities get online are handing private companies opportunities to discriminate based on content or pricing in the future, unless a solid legal framework is in place.

To learn more about the new U.S. rules and the upcoming votes in the E.U., see here and here. Our colleagues at the Greenpeace Mobilisation Lab have also put together a great overview of the intensive, well-coordinated campaign that helped turn the tide for net neutrality in the U.S.

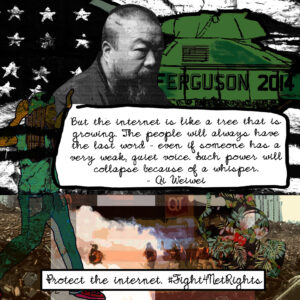

Illustration by Sandra Khalifa (via 18mr)